Creativity, culture and city life in 2020 and beyond: an interview with photographer Sven Marquardt

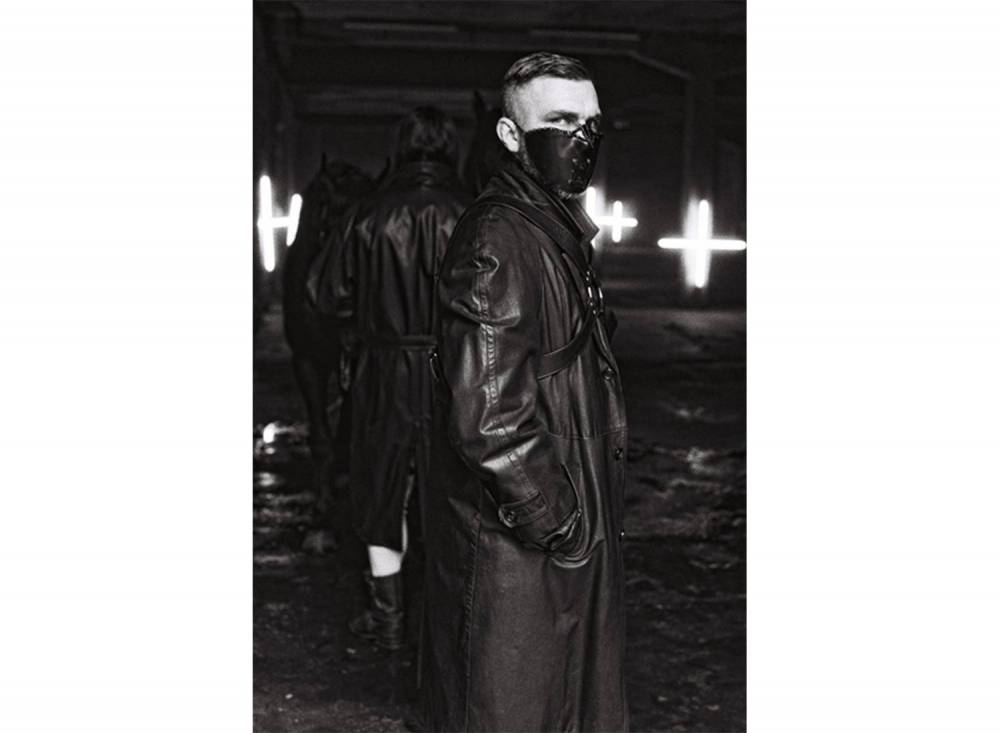

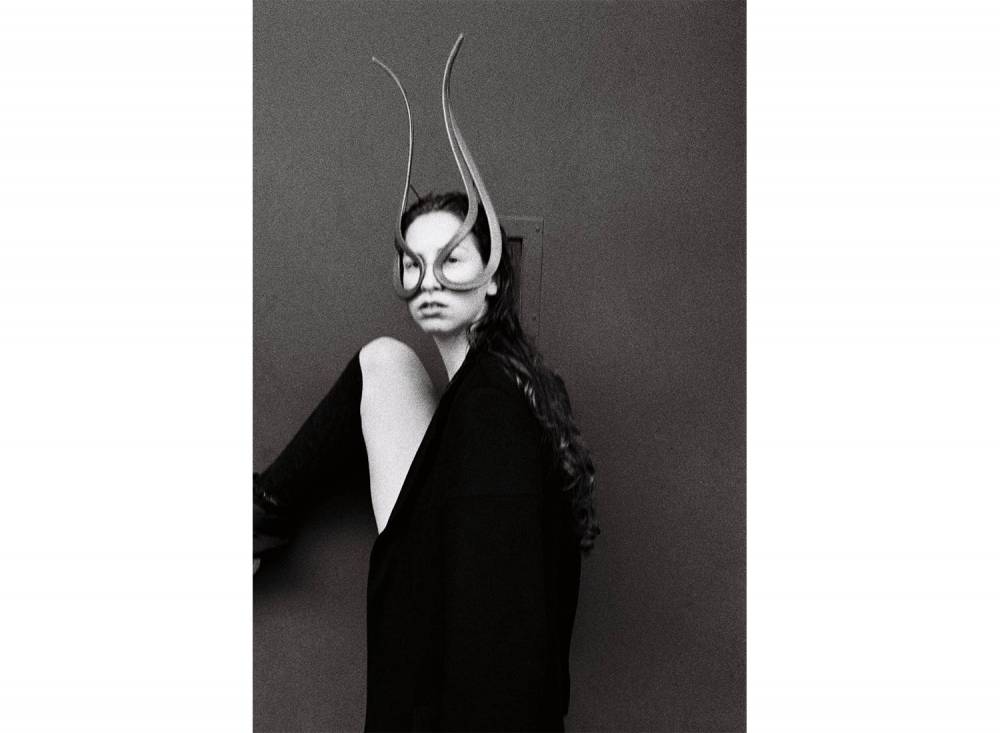

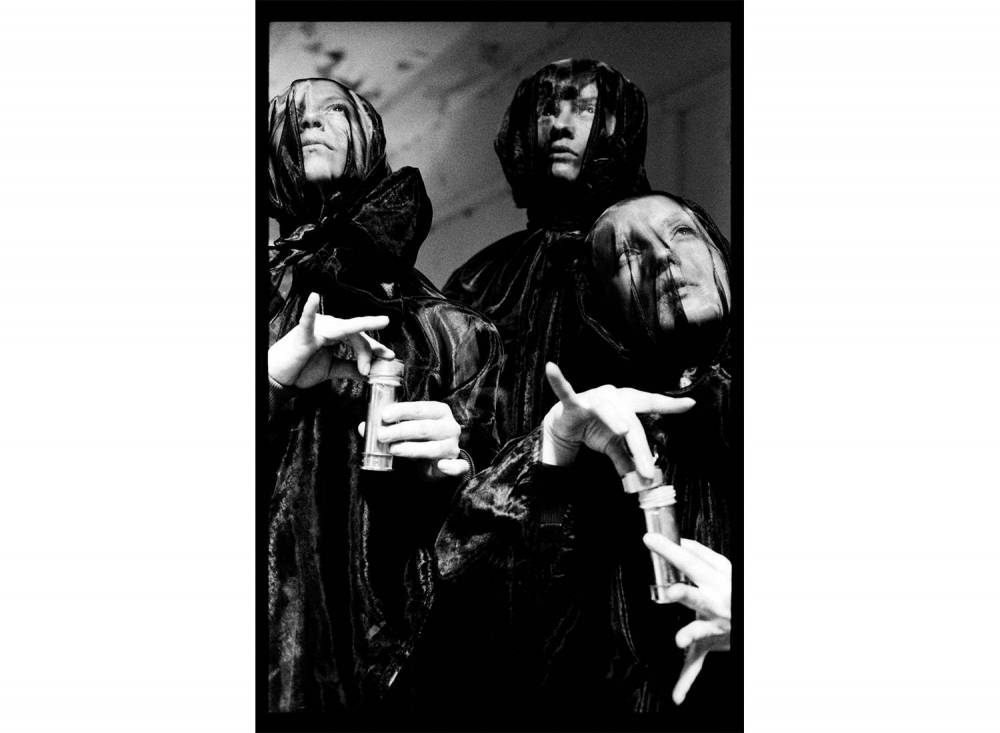

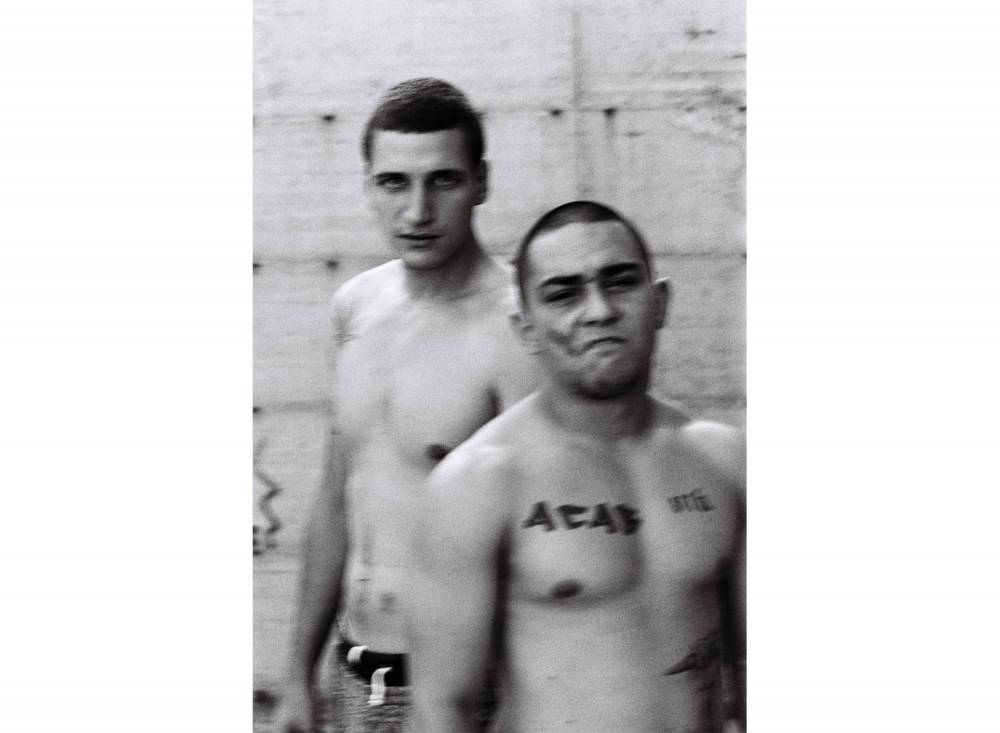

Sven Marquardt is one of the most prominent figures of the Berlin underground scene. Back in the ‘80s he was portraying GDR’s underground scene using black and white film and an analogue camera. These days he is steeped in the club scene which he perfectly captures mostly in black and white. You might also know him from the documentaries Beauty and Decay and Berlin Bouncer about his photography, his contribution to the infamous Berlin club scene and making Berghain one of the most famous clubs in the world. We spoke to him about his art, changes in the cultural world and how the pandemic has affected it all.

by Ana Maria Carabelea

2020 turned off the lights on the cultural scene around the world.

For the first time since the Fall of the Wall, Berlin went quiet as the vibrant city life was abruptly paused. Faced with even more uncertainty than usual, yet resilient as ever, the cultural world found ways to make noise in the silence of the pandemic.

The exhibition Studio Berlin – a collaboration between the famous techno club Berghain and the Boros Foundation – turned the club’s dancefloor into an art gallery. Studio Berlin gathered over 100 Berlin-based artists in a gesture that recognised the importance of saving the city’s cultural scene in all its forms. All ticket sales were directed towards saving the notorious Berghain.

We spoke to one of the artists involved in the exhibition, who is also one of Berghain’s gatekeepers: Sven Marquardt.

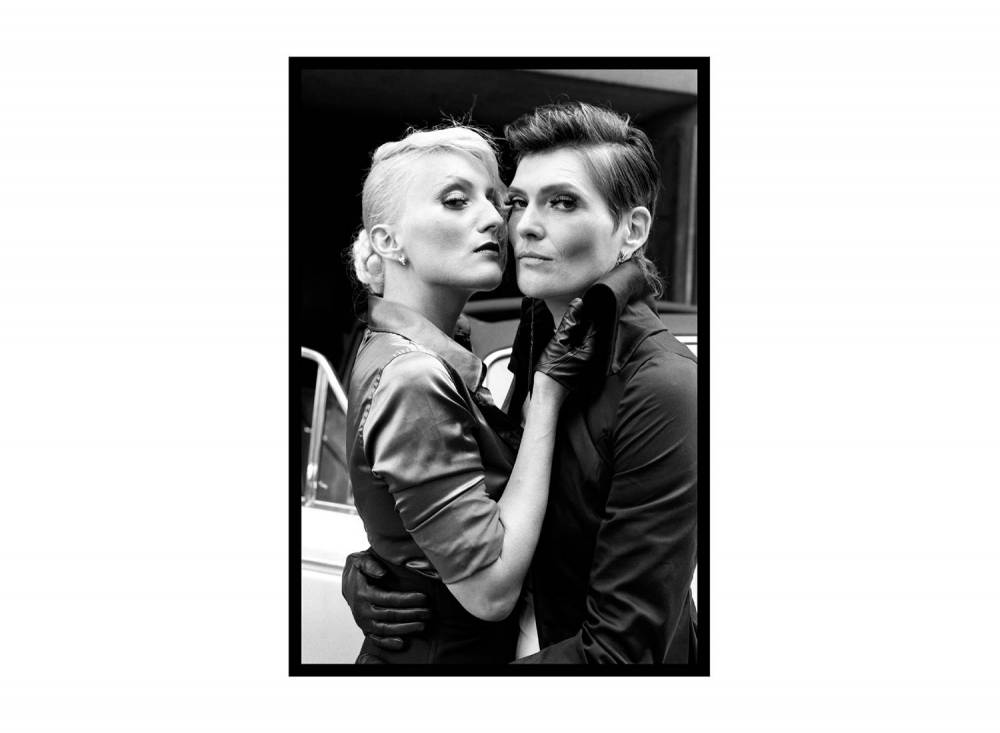

Marquardt started photographing the GDR’s underground scene in the ‘80s using black and white film and an analogue camera. He remains faithful to both until this day.

As he journeyed through the Punk and New Wave scene, the transition period that followed the Fall of the Wall and the birth of Berlin’s club scene, his photos have gained the corners and edges that became his hallmark.

Marquardt parted temporarily with photography in the ‘90s, taking time to understand the new scene emerging in a city now freed from restrictions. This period of research, observation and immersion into the club scene has allowed him to create work that captures the Zeitgeist of an ever-changing city.

Now an acclaimed photographer, Marquardt is still associated with the club culture. He straddles both worlds and seems to feel most comfortable in between the two. In addition to this, Marquardt also worked on multiple brand campaigns for the likes of Baldessarini and Hugo Boss, bringing the same aesthetic to his commercial work.

With both his worlds in a state of slumber, he told us what 2020 was like for him and how he sees the future for himself, his fellow artists and culture makers and cities, in general.

Last year was different, to put it mildly. People reacted to the changes in ways they themselves might not have expected. What has changed for you? Did you find out anything new about yourself from your reaction?

Everything changed, not just for me and those in the cultural industries, but indeed for everyone.

The doors of the club closed. The agency that represents me as a photographer, Ostgut Berlin, saw a sudden shut-down when everything was cancelled. My life consisted of exhibitions around the world and giving lectures in Berlin and Florence. Everything I do requires the public, and suddenly it wasn’t possible to do any of it anymore.

Probably like everyone else, I tried to make use of this time. I made a film called Isolation in which I have recounted how things were going for me. I filmed recurrent scenes and rituals in my home, wilting flowers or burning candles. It’s vanitas work.

The irony was that suddenly, I had a lot of time to photograph, but these times have not made me particularly creative. I miss the input from the outside world, from life around me. I am not one to withdraw from the world. I do it from time to time, but this forced withdrawal in isolation didn’t inspire me.

Despite the tragic first lockdown, there was a sense of adventure in it, in contrast to the present moment when everything is very still, and that illusion of adventure has disappeared.

Many people have seen this as a time to slow down, think about the situation, reflect on what to do next, what they have done so far and how grateful they should be for the lives they had before. But I have always had this feeling. I didn’t need to lock myself away for ten months to discover that. This stillness is not inspiring; it’s merely a strange wait.

Throughout the years, many Berlin clubs have closed, but many have established themselves as cultural institutions, Berghain being one example. You previously spoke about the uncertainty and decay that marked the birth of the Berlin club scene. How do you see Berlin’s nightlife come back to life after 2020? Do you think the new normal will carry the same transiency and uncertainty that marked the club scene in the ‘90s?

Decay has been at the centre of a few of my projects. It even became the theme of the documentary about my work by Annekatrin Hendel.

I believe the theme of decay is always on our minds and becomes more acute with age. More so when you have worked as a photographer and, in parallel, at the doors of Berlin nightclubs for almost three decades.

Of course, there is a sense of hope in the comeback, but we don’t yet know what that will look like. In an article I read a couple of days ago, one of the Club Commission representatives – an organisation representing club owners – said that, as clubs were the first to close and will probably be the last to re-open, resuming won’t be easy. I don’t think that things can go back to being the same as before after such a long time. The scene had been built bit by bit and was the result of changes in state policies and a generation’s particular mindset. It’s now gone. How will it go on?

I believe it will because, as we’re told, each crisis is also a new chance. I don’t think it will be the same, though, and I don’t believe this concerns me anymore. I am in my late 50s, and there is now, fortunately, a young generation that has the reigns and can create something new.

Even if I might not be at the centre of it, Berghain will remain my basecamp and the club culture the starting point for my work. This club feeling allows me to grow old in a different way.

You’re bridging between the art scene and the club scene. You’re the only visual artist represented by Ostgut and were also part of the Studio Berlin exhibition, which was a great example of solidarity within the cultural scene. Do you think we’ll see more of that happening in the future? Has the pandemic given us the time to stop and think more about how a thriving, lasting cultural scene can emerge?

The Studio Berlin exhibition gathered more than one hundred international artists who all live and work in Berlin and have not had the chance to show their work in the past year. Studio Berlin came about as a response to a crisis.

But in fact, long before Studio Berlin, Berghain had collaborations with the National Ballet and hosted a performance in Halle am Berghain with a stage designed by Norbert Bisky. The ten-year anniversary exhibition called Ten included ten artists who were also involved with the club, like Brandenburg, Bisky, and myself. I know that it’s a lot more challenging for smaller clubs to host such things as a performance of the National Ballet, but I do believe it was a motivation for other clubs to mix the club scene with the art scene.

I have always associated Berghain with art and culture. Working with teams of professional dancers and models on other projects always reminded me of Berghain. It might be surprising to many people, but running such a place at the weekend, and in addition to that hosting concerts and exhibitions, involves a lot of work behind the scenes. I think there are similarities between high culture and club culture, and that’s why I’ve always been able to work in both. For me, these two worlds are connected, even though at the beginning of the ‘90s, I put away the camera and was only consuming club culture. I don’t think it was a loss. I simply needed time to understand, feel and grasp this new country. In a way, 2020 was the same.

But overall, in the cultural scene, we’ve seen efforts to create bridges.

I worked on a project with Friedrichstadtpalast in Berlin. They had to close and could not perform, so they put together an exhibition titled Stageless with photos I had taken of the dancers.

Many places invited DJs to play and live-stream, like the Naturkundemuseum (Natural History Museum), power plants, or the Bunker of the Boros Collection in Berlin Mitte that hosted United We Stream. There was a nice blend between the artworks in the space and the music played by the DJs. It was great to see such a performance but also hard to watch it on an iPad and not in a club. But it does transmit a bit of that feeling. Not the best, but still, things did come to life, which created a chance for something new to emerge – even in 2020.

How did it feel to see the club space turn into an art gallery? Do you see any downsides to these collaborations?

Sad. Really. Having thousands of guests for a soft opening was out of the question. Due to the restrictions, the 118 artists exhibiting could each bring only one guest. And that was it.

I was walking through the exhibition before the opening, and I remember thinking we weren’t really ready to open. As always, with an event involving so many artists, the curators have taken on a massive challenge, but the result was truly remarkable in the end.

Despite this, the opening day felt like the end of an era. It may sound melodramatic, but the feeling was that the club had turned into something else all of a sudden. I wouldn’t say it turned into a museum because they did a great job preserving the essence of the place. The exhibition didn’t have a museum feel about it, artworks were not framed and exhibited in a traditional way, but instead, they blended in the space. However, anyone who had been there for the past 16 years was going to have mixed feelings about this.

How do you think cities can be brought back to life after the pandemic, and can Berlin still be an example of how to preserve an underground culture for other big metropolises?

It’s going to be interesting. I don’t think we can press a button and everything will be the same as before. But I hope there is also a chance in these times for a new beginning and a reconsideration of values. I hope these values are not merely still, dormant. Berghain and the Berlin club scene always stood for diversity, and I hope that people will come back and reclaim those free spaces. I think alternatives are essential, and allowing frictions in society is critical. It’s important to fight and take back these free spaces. I believe – in fact, I know – the young generation will do that.

Even though I didn’t know New York back in the days when everyone thought it was great, for me, the time in New York was still exciting. When I now see photos, I think to myself: God, everything is shut. The sight of masked people on the streets is dreadful. It reminds me of those science fiction blockbusters.

How do you now recover a city? I think we have to work a lot on the recovery. It’s worth it though if it means recapturing the cities’ vibes. This historical moment has changed the Zeitgeist in the entire world, so we can’t expect the feeling to necessarily be the same. Different times will come, and this period will be marked as a turning point in the history books.

You’ve travelled and exhibited your photos in many parts of the world. You’re always associated with Berlin and the Berlin club scene. Do you think your images are interpreted differently elsewhere? Have you had any particularly surprising reactions?

As you say, most of the invitations I get are connected to Berlin and my persona and personal biography. The interest in my work and my talks always makes me feel appreciated.

There were, of course, places in which I didn’t feel at ease. How do you share a space with strangers in a culture that is not yours? You’re a guest that looks around and keeps to themselves for fear of behaving inappropriately.

And the audiences’ reactions in these places are also different, sometimes a bit cautious, especially in places where freedom is not a given. This should never be the case, and I think we should always fight against this.

One unique encounter was in Lagos, Nigeria, where I did an audio-visual installation in collaboration with Marcel Dettmann, titled Black Box. It was a combination of his sound and my images. After the opening night, people started dancing in front of this black box. It was like nothing I had experienced or seen before.

Do you see yourself photographing elsewhere?

I never travel with a camera, so I never take photos on my trips.

I lived and worked for two months in Belgrade and Sydney. But these stays were a bit too short for what I had in mind. I wanted to see if my photos, my compositions and portraits would work elsewhere.

In Sydney, the project pushed me to experiment with new ways of working. I thought I’d fail. I thought I couldn’t do it because I had no contact with the scene. But regardless of whether I managed or not, it was a unique and important experience.

The culture in Belgrade was more familiar. It had an Eastern European feel and reminded me of Berlin in the 90s – while it was still Serbia, still different. I managed to do a cool project there even though everything was new, and I had to map out the entire process. It was helpful to have someone there to take care of all these details. It takes so much time to think of everything, and I couldn’t have done it by myself in that timeframe. In the future, I’d plead for more time.

In fact, I thought about trying to live elsewhere, but somehow it never worked out. All my photos came into being in Berlin with the input of this city.

In your photographs, you want to capture the ways in which people are different (das Anderssein). This difference is measured against the current social context. Can you tell us what this alternative lifestyle means for you?

What I personally see, live, and induce with my photos is obviously very different.

The alternative lifestyle has always been the norm for me. I come from a conservative family. When I dove into the gay subculture and, later in the 80s, into the bohemian Punk and New Wave Prenzlauer Berg scene, I ultimately parted with this conservative lifestyle. My life experience and work in the years after that were indeed alternative. Then came the Fall of the Wall, and the club culture suddenly emerged in Berlin, with a feeling that had never existed before.

Despite always being the ‘normal’, it never stopped being exciting, but it also came at a cost. It’s my only truth, though.

At the door, you’ve been heard to say, “this is not the right place for you”. For who is Berghain the right place?

The door isn’t a one-man show. With time, people started recognising me and associating me with the door. But neither my colleagues nor I stand at the door for our interest, but the ethos of the place. Berghain stands for diversity and freedom, for being yourself and being able to be authentic in peace. What we try to protect is important for the people inside. It’s for them to feel unhindered. If that works, then our work is done.

It feels terrific to hear from people in the club or even people on the street that they’ve had a good experience.

It seems like such a long time ago, though. I don’t miss the nights and the late work at my age, but I do miss the place in itself with its energy and its exchange, the agency, the musicians, all the DJs, the photography work I’ve done for them.

On any given night, you select the crowd to make sure it’s in line with the ethos of the club. You’ve been compared to a curator. Do you sometimes find yourself looking at the crowd with the eye of the photographer looking for the perfect composition in an image?

It’s hard to separate the two, but it’s about the club and not about Marquardt at the end of the day. Of course, I look at the queue or the people through a personal lens, but I use it to represent the ethos of Berghain. I never see a potential composition in it. The night does inspire a lot of my photography. Someone once said that my photos are night photos. They do have a granular aesthetic, but I use only daylight and an analogue camera. I need at least the break of dawn.

In my models, I search for character and authenticity. This is the reason why I find it interesting to work on fashion projects with young professional models. The two projects I did with dancers were also great. I was fascinated by the discipline, the bodies, the radiance, the character on the stage.

If you had to, what would you choose, the camera or the door?

It’s tough. The camera has been in my life longer and will probably remain longer than the work at the door. I’d say that when I leave the door, or it leaves me, the camera will stay. But for a long time, my identity has been defined by both, and I am proud of it. The door has opened many opportunities for me, but it has kept others closed because, for many, I’ll always be a bouncer. This kind of polarisation isn’t necessarily bad though, it’s part of my life.

What does 2021 look like for you? Have you got any plans, any projects you started working on in isolation (apart from Isolation)?

I am very cautious because the disappointment that comes with having many things cancelled is quite daunting. I think we’ll need to relearn things. Opportunities and projects are important. I’m at the start of a few different projects that aren’t abroad. Other things are in the planning phase. The only concrete plan is an exhibition in Beelitz in May.

I really hope the Studio Berlin exhibition will reopen in March. We were only open for a couple of months before the lock-down started in November.

For the rest, I’ll have to take it one step at a time. I believe the next months will be decisive, and I’d rather plan bit by bit.

Now I remember, I applied for a residency in autumn 2021 in Istanbul. I will get an answer in March. In any case, it will be an adventure, a new country, a city I’ve never been to before, a great challenge, and if not, I still enjoyed the application process. Hopefully, something will come out of that regardless. But I try to be very cautious when planning anything at the moment.