The academization of creative processes

In our time, where everything is potentially at the tips of our fingers, one click away, what does this mean for art and design education?

Are institutions a prerequisite to be successful with creative work or are they places where a wild, creative mind is being tamed?

Are they leftovers from old times in which higher education was available only for a selected few or an inclusive, openminded playground for everyone?

Since the first art academy, the Accademia Delle Arti del Disegno, was founded during the 16th century in Florence, the amount of artistic education institutions has grown to an overwhelming number. In Europe alone there are more than 300 institutions offering Bachelor, Master and Phd degrees in the visual arts. This has led to a flooding of the “creative industry” (a term, coined by Tony Blair when he set up a task force to define and measure the economic value of creativity in 1997).

Way more highly educated artists and designers graduate than there are jobs available. Even though the opportunities have grown, one burning question is: grown for whom?

Regarding the aspect of accessibility, geography makes a huge difference: some countries offer programs with low or no tuition fee. However, in countries like the United States a rich family background, a scholarship or a massive student loan is required to have access to education. But even in countries where it’s more affordable, studying art and design (or any other subject) seems to be reserved for privileged few. Especially in the design context, exclusivity has a larger impact on society than one might think. In his book Caps Lock (Valiz, 2021), Ruben Pater states:

“The problem with unaffordable education is that voices from lower income communities are less represented in society. The voice of the uneducated, the poor, the marginalized are mostly absent from history books, for this very reason. An expensive design education could lead to a wealthy class of designers who assume their audience is also well-off, which can obfuscate some of the most important social issues in society such as inequality and privilege. Viewing education as a monetary exchange overlooks the possibility that education is perhaps not only about preparing for work. The German word for education is Bildung. It means a process of personal and cultural maturation, both in a philosophical and educational sense. If we see education not merely as a commodity but as a familiarization with public culture and knowledge, then it is logical that everyone should have access to it. Education is therefore also a commons, a public source of knowledge exchange which has become more and more enclosed by capitalism for the purpose of profit.” (p. 356-357).

So, an art and design education with limited access bears the risk to result in an echo chamber of those, who where thriving in the first place.

In addition to the question of in-and exclusivity, the question arises as to wether it is necessary or even possible to teach art.

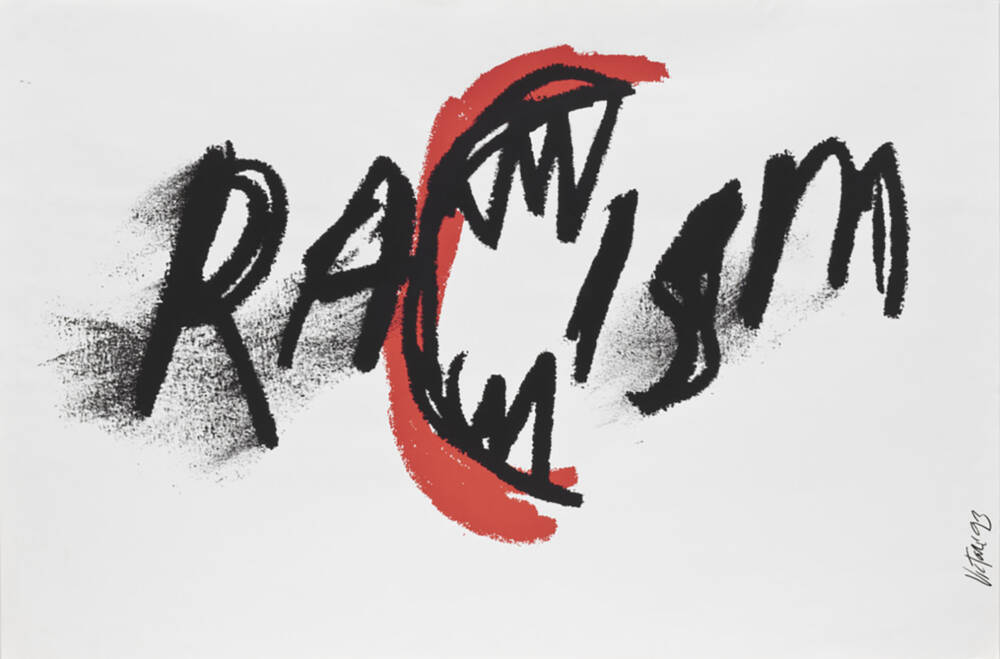

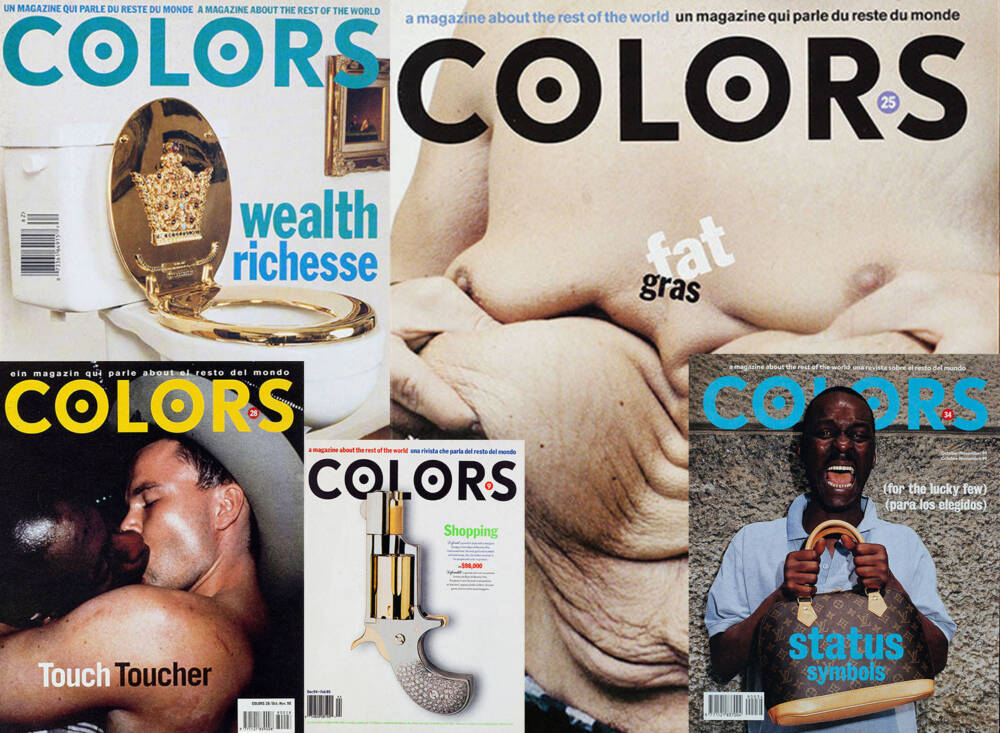

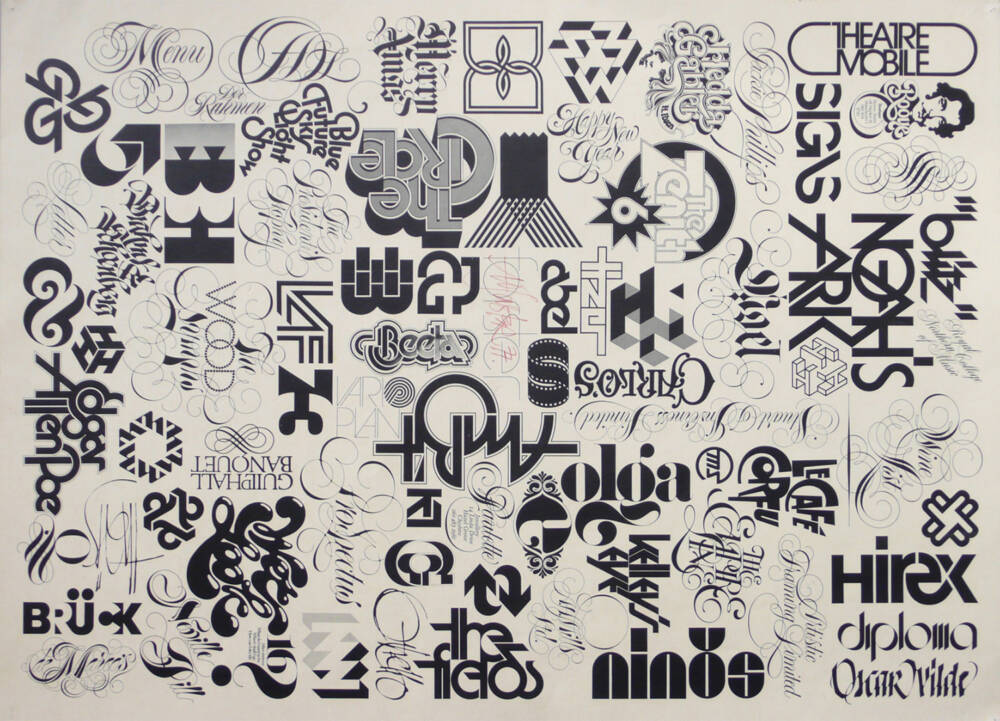

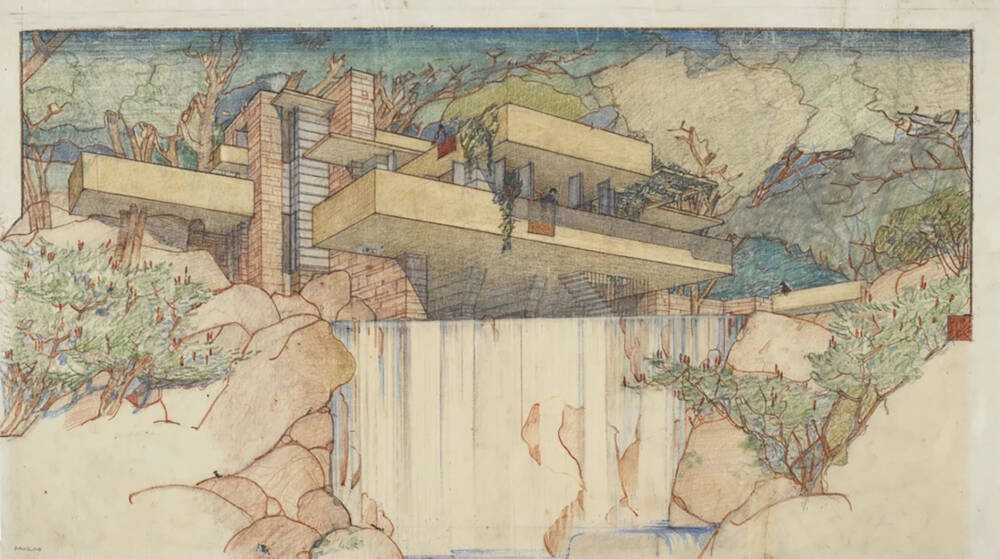

Both, in the design and the art world, there are many examples of personalities, who made it without a traditional education. To name a few, from a variety of fields: David Choe, Tibor Kalman, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Frank Lloyd Wright, Tony Forster, Sophie Calle, David Carson, James Victore, Frida Kahlo.

Carson, who had a major influence on graphics in the 1990s answered to the question wether creativity is teachable: “I’m not sure you can teach creativity: you either have that eye or you don’t.”

Most of the creatives mentioned above lived in a time during which the internet was either non existent or just beginning to reach everyone’s daily life. One could argue, that with today’s opportunities, allowing to literally learn any program from home via YouTube tutorials, to become highly educated and skilled without a degree is easier than ever.

Sometimes the phenomena of students aiming to copy their professor’s style can be observed during diploma shows or open studios. Some students experience a manipulation into a certain direction, away from the initial personal approach.

Hence, the initial question remains: can creative processes be academicized? A missing creative impulse can’t be substituted by a degree. Creative techniques however, will most likely not be taught at an art academy, because often the expectation prevails, that students already know how to work in their medium. Rather than learning techniques, it’s more about the creative ideas and the conceptualization thereof. In case technical improvement is whats missing, self-teaching is a good solution. Mostly, it’s about trusting the process, knowing the worth of one’s work and going out into the world with it.

Is there a need for highly valued qualification to legitimize artistic work? If so, who is to judge or measure the quality of art or design?

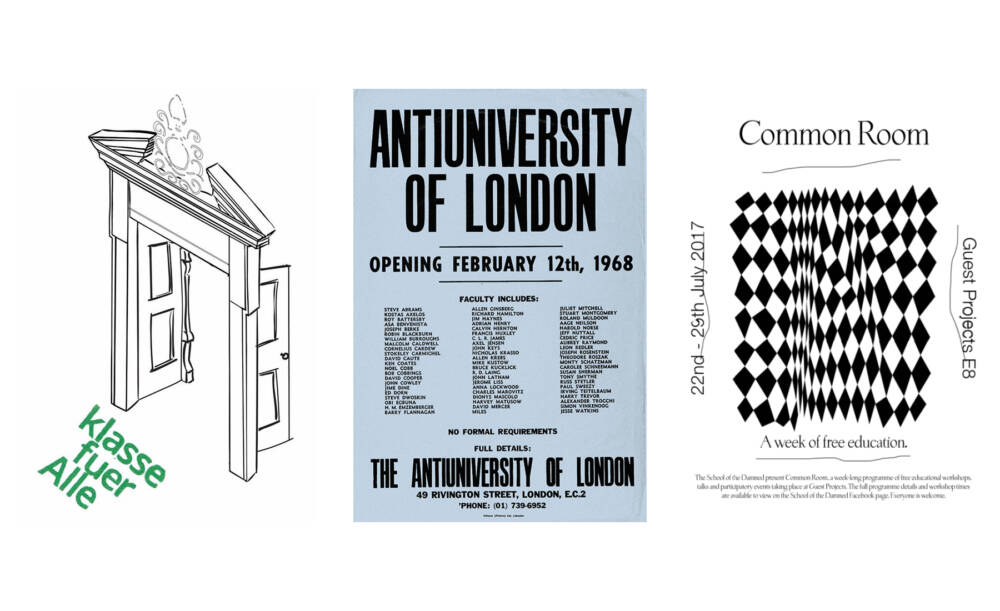

Maybe it is time to found truly free, accessible, and collective educational opportunities in the field of visual arts. It has been proven that alternatives are possible — from the The Antiuniversity to contemporary concepts like the School of the Damned, Open School East or the Klasse fuer Alle (which is embedded into the institution of the angewandte university Vienna, but has a libertarian approach). These approaches have the potential to replace old concepts around creative education.

Concluding, there is no right or wrong path. Education in the visual arts can be merely a tool, the creative idea is what distinguishes an original work from the masses — a unique visual language. To some it is easy to find this in an educational context, others might find it constricting and flourish all on their own. Neither is a guarantee for success, but authenticity, originality and honesty are.

Image Credits

Cover: © David Choe

Images Top to bottom: © James Victore, © colors magazine / Tibor Kalman, © Tony Forster, © JR, © The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives

Collage: © Klasse für Alle © The Antiuniversity © School Of The Damned